By Melanie Woods, April 27 2017 —

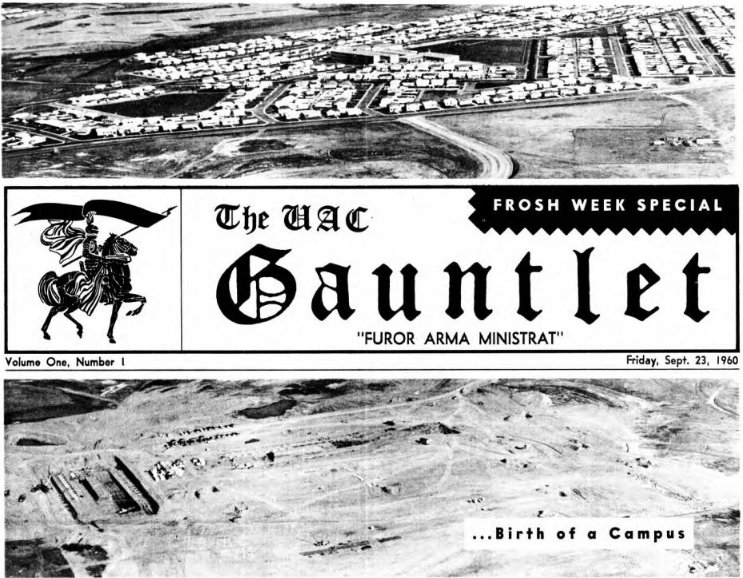

On Friday Sept. 23, 1960, 1,300 newspapers appeared on the stands of the newly minted University of Alberta, Calgary (UAC) campus. While the campus only consisted of two buildings back then — now known as Science A and Administration — the population was blossoming. The campus looked forward to welcoming over 1,000 new students for the 1960–61 academic year.

Fifty-seven years later, the University of Calgary’s population totals well over 30,000 and dozens more buildings have sprouted across campus. But some things never change. University presidents still remind us to “lift up our eyes,” the Dinos still play sports and the Students’ Union and university still bicker over MacHall.

As the newspaper of record, the Gauntlet has documented all of the university’s changes since that first issue on Sept. 23 1960. And through that time, the Gauntlet has changed too. In the past 57 years, the Gauntlet has switched publication dates, times and sizes. It has added new features and discarded others. In the 1990s it launched a website — www.thegauntlet.ca — and has also expanded through social media, radio and video.

This year, the Gauntlet stopped printing weekly for the first time in its history and will move to a monthly magazine with a daily updated website. On the eve of this new chapter, we decided to look back on some of the key turning points in the history of the Gauntlet and the U of C.

Sept. 23, 1960: Birth of a campus and a newspaper

“FROSH, WE ALL— In a sense, we’re all freshmen this year, as the Calgary university of Alberta packed up kit and caboodle to move to its new grounds. But it’s not physical buildings which necessarily sets apart the university from, say, the high school. It’s the people that inhabit and the ideas that are born in those physical edifices that spell the crucial difference. Still, this year should be a unique one for us all. The buildings are totally alien to all, strange and unexplored. Every day will bring new mysteries to be solved, new adventures to be enjoyed, new tribulations to be suffered and survived.” Maurice Yacowar, Sept. 23, 1960.

The Gauntlet wasn’t the first student newspaper at the UAC. That distinction belongs to the Cal-Var — short for Calgary Varsity — established when the UAC was still located at the campus that is now the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology. In 1948, then-president of the UAC SU Frederick Cartwright established the Cal-Var Commentary, which published until 1960, when the UAC moved to a newly minted northwest campus.

To usher in a brand new era at the new campus, the SU decided to publish a new newspaper, releasing volume one, issue one of the Gauntlet. In its early years, the paper’s small office was located in Room 027 in the basement of what is now the Administration building. The paper was funded by the SU, had a circulation of 1,300 copies published weekly on Fridays and presented the same slogan it does today — “furor arma ministrat,” Latin for “rage provides arms.”

Its first editor-in-chief was Maurice Yacowar, then a second-year English student described in his introduction as “the man who has dedicated himself to the conquest of vice, corruption and complacency.” Yacowar would also go on to have the distinction not only of being the first Gauntleteditor, but also the the first to be fired from the job.

Yacowar faced heat for a short story published in the Gauntlet’s first literary supplement, Callidus, on Feb. 14, 1961. The story featured depictions of the loss of virginity and sexual intercourse and caused widespread outrage across the campus and the city. The supplement was deemed illegal due to controversy over its publishing and was seized, with Yacowar fired by the SU shortly after.

The SU claimed the firing was due to a multitude of reasons concerning editorial control of the Gauntlet, but in a Feb. 22 editorial, new editor-in-chief Alan Arthur questioned the move.

“If, as Students’ Council asserts, this had nothing to do with their action, why did they hold a special meeting two days after the seizure, instead of waiting until their next regular meeting to consider Mr. Yacowar’s fate?” Arthur wrote.

So would begin a long and complex relationship between the Gauntlet and the SU.

The 1960s–70s: Growing into an independent press

“Control of the major communication media should not rest with the governing body, whether that body be the students’ council of a university or the government of a country. We’re talking freedom of press. The staff of this newspaper will not be forced by [Students’ Legislative Council] or its executive to publish anything. We will publish what we deem to be the proper content and lineage.”The Gauntlet Editorial Board, Nov. 22, 1978

The Gauntlet underwent many changes in its early decades. It changed its slogan to “the people’s newspaper” in the mid-1960s. The paper also moved from Friday to Wednesday in terms of publishing dates, then experimented briefly with publishing twice a week in 1972. That only lasted eight issues, but they went back to the twice-a-week model the following year, publishing on Tuesdays and Fridays for the next few decades.

But during all these small changes and editorial board turnovers, tensions grew between the Gauntletand its readership, as well as the Gauntlet and the SU. The paper faced a defunding referendum vote in the fall of 1969 that proposed stopping SU fees from going to the Gauntlet.

“When the Gauntlet was a bland, conservative rag nobody complained about shelling out two bucks a year for it. But now that we are disturbing a few minds, there is suddenly a move to smash us,” editor-in-chief Jimmy Rudy wrote in an Oct. 22, 1969 editorial about the referendum.

The Gauntlet returned in September 1970 a little haggard, but quickly recovered. However, the tense relationship with the SU persisted, simmering beneath the surface. In 1978, it reached a boiling point.

On Nov. 22 of that year, the Gauntlet published a front-page editorial titled “Gauntlet editorial – newspaper principles.” In the piece, the Gauntlet editorial board detailed what they deemed to be undue influence from the SU on the paper’s content, particularly regarding advertising. The SU executive had struck a policy to dictate and control the ad presence in the Gauntlet. The Gauntletclaimed this went directly against the SU’s constitution, which stated “the editor shall control the content of the Gauntlet.”

On Nov. 29, the SU executive published a response on the Gauntlet’s cover. “It is our interpretation that the SU is the ‘business manager’ of The Gauntlet, and the paper’s editors and staff are not empowered to decide all business matters,” John Lefebvre wrote on behalf of the SU executive. The Gauntlet brought its response to the Review Board, which ruled on Jan. 10, 1979 that the union had delegated ad lineage responsibility to the Gauntlet editors, thus ending the conflict.

A month later in the 1979 SU election, the Gauntlet ran a referendum campaign to gain autonomy. The question asked students if they would be willing to contribute $1 a year for full-time students or $0.50 a year for part-time students to support an independent Gauntlet Publications Society. “Both the operation of the SU and the operation of the newspaper are becoming more and more sophisticated,” co-editors Scott Ranson and Mark Tatchell wrote in a Feb. 2, 1979 editorial. “Both are now worthy of their own autonomous, individual existence.”

On Feb. 16, students voted over two to one to fund the autonomous campus newspaper. The society held its first Annual General Meeting on April 11, 1979. In the final editorial of the year, Ranson called the referendum win a “total victory.”

In the first editorial of the following year on Sept. 6, 1979, new co-editors Michele Bestianich and Rory Cooney welcomed students in an editorial titled “Autonomy at Last.”

“Now more than ever the Gauntlet is a student newspaper. Whether the Gauntlet continues to strive for responsible journalism, or succumbs to financial and especially staff instability is up to the student body,” they wrote. “The hard work of past Gauntlet staffers has formed a base to work on, and we hope students will participate as the Gauntlet continues to grow.”

1980 to now: An evolving Gauntlet

“A year from now, the issues reported in the Gauntlet will have been forgotten by most of us … but they will, nonetheless, affect us in some way. That is education.” Roman Cooney, April 11, 1980

The ‘80s and ‘90s marked continuing change for the Gauntlet. Publication dates, frequency and numbers shifted. The Gauntlet started to print in colour in the 80s and moved to full-colour newsprint in 2015. The Gauntlet’s website was introduced in 1998 and its focus on social media spread across various social media platforms over the following two decades.

In 2001, the Gauntlet moved from its offices in MacHall 310 — now occupied by CJSW 90.9 FM — to its current location at MacHall 319, just above the Den and Black Lounge. This year, the Gauntletreceived $492,694 in Quality Money funding to renovate and update the space.

On Jan. 14, 1993, the Gauntlet published its thousandth issue. At the time, the newspaper had a circulation of over 13,000 print issues a week. In its final year of weekly publication, that number had flatlined at 6,000 a week.

However, the web presence that started in 1998 has skyrocketed. Currently, the Gauntlet receives around 40–50,000 hits a month on its website. More people than ever are talking about articles online, retweeting tweets and engaging with Snapchats.

The Gauntlet’s slogan is still “furor arma ministrat,” which originates from Virgil’s Aenid and translates to “rage provides arms.” In the Gauntlet’s case, the rage is a desire to inform, and the arms is student press — even as that form evolves and shifts.

This edition marks the first time the Gauntlet will publish monthly. It’s the next chapter in a very long, very complicated story. Like many changes before this — from an editor fired over a short story about sex to a fight for autonomy — the Gauntlet will continue on, as it has for over 57 years on the University of Calgary campus.